Modeling State Recognition as a Displacement Stabilizer in the Horn of Africa

Greater Institutional Engagement with the Breakaway Republic of Somaliland Could Help to Address Migration and Security Issues in Somalia

By Bennett Iorio

Nearly all political maps of the Horn of Africa are inaccurate: They show Somalia as a single entity; an unbroken outline running from Kenya in the south to Djibouti in the north, including the bulk of the Horn of Africa. In practice, modern Somalia contains distinct political units. Puntland, to the northeast, is semi-autonomous, and in 2024 announced that it would “act independently”1 from Somalia. Somaliland, to the northwest, officially declared itself independent in 1991 and has operated separately for three decades.2 Covering an area of 176,000 km² and with an estimated population of some 6.4 million people as of 20243, Somaliland has regular elections, its own security forces, a functional court system, a political and administrative capital in Hargeisa, and a growing port economy centered on Berbera.4

Source: Somalia’s Federal Future Layered Agendas, Risks and Opportunities, Chatham House, September 2015 p.3

Despite its extensive track record operating independently, Somaliland is not recognized officially by any state or international body. It is not a member of the African Union, the United Nations, or any multilateral financial institutions. Discussions about recognition have surfaced intermittently, particularly within U.S. foreign policy circles, but have never advanced beyond informal consideration. Currently, there are reports that some factions within the U.S. administration of Donald Trump are again exploring the idea of formal engagement with Somaliland. But Somalia opposes recognition stridently, condemning recognition attempts as violations of its sovereignty, and reaffirming that Somaliland remains an integral part of Somalia.5

This discrepancy has very concrete consequences. Somaliland has a much harder pathway to accessing development funding, climate finance, and formal security cooperation, either internationally or internally. It also hampers the efficient management of irregular migration within and out of Somalia, with spillover consequences for neighbouring states and as far afield as Europe.6 For example, according to UNHCR data, by 2023 there were over 714,000 Somali refugees living in neighboring states, including 308,000 in Kenya, 276,000 in Ethiopia, 70,000 in Uganda, and 47,000 in Yemen, in addition to nearly 3 million internally displaced persons (IDPs) inside Somalia. Kenya’s Dadaab complex alone hosted more than 426,000 registered refugees and asylum-seekers as of early 2025, the majority of them Somali.78

Due to lack of recognition, Somaliland cannot enter into international agreements on migration or border management. When a territory is not recognized as a state, other countries and international bodies treat it as though it does not exist as a legal entity. Recognition is what allows a government to enter treaties, join organizations like the UN or African Union, open embassies, access international courts, and receive direct development or climate finance. Without recognition, a territory cannot sign binding international agreements, cannot exercise sovereign rights over its borders, airspace, or maritime zone in international law, and cannot be a counterpart for aid or security partnerships. Instead, all official dealings go through the “parent state” – in this case Mogadishu – even if it does not control the territory in practice.

What this means for Somaliland is that it cannot receive multilateral development financing. It cannot patrol or legally assert control over its maritime territory. Most importantly, it cannot function as a formal end point for displaced people fleeing conflict or drought in southern and central Somalia. Somalia’s fragmented legal systems and limited capacity result in inadequate responses to human trafficking and smuggling, and the absence of unified migration governance complicates prosecution, reception, and coordination for irregular migration, especially over the internal border with Somaliland. The practical figures around the consequences of lack of recognition are stark: International aid and climate finance are routed through Mogadishu, leaving Somaliland excluded; in 2016 Somalia received $1.3 billion in ODA, but almost none was allocated to Somaliland.9

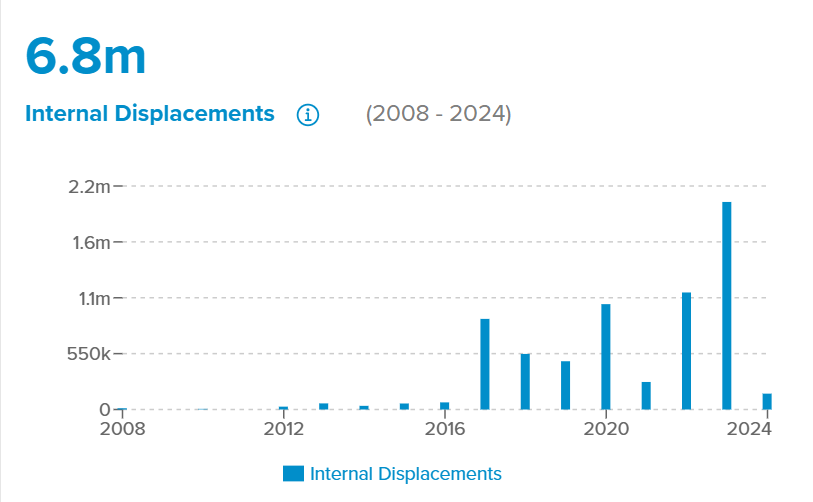

Following years of civil war and unstable government, the southern half of Somalia is wracked by overlapping problems arising from disorder and climate change. The number of IDPs hit a record 3.9m in 2022 and was still 3.1m by 2024, according to data published by the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre and the UNHCR Protection and Return Monitoring Network (PRMN).10 Many movements follow established northbound routes into Somaliland. These movements are not random, spontaneous or chaotic, but instead follow corridors shaped by road networks, political boundaries, hazard zones, and the availability of services.

Source: Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre, Somalia

Preliminary research (not peer-reviewed) from a multi-university collaboration (Sousa et al, 2025)11 has reconstructed over 20,000 such movements across Somalia from February to June 2025, studying both the patterns and exposure to violence, drought, and food insecurity along the way. As of 2023–2024, Somaliland hosts between 650,000 and 800,00012 IDPs, out of a national total of roughly 3.9 million. This places its share at about one-fifth of Somalia’s displaced population.

Read alongside the political geography of the Horn of Africa, this shows that Somaliland already serves as a functional – but unrecognized – node in the Somali displacement network. It is a place people go to escape, but its lack of sovereignty restricts what it can do once they arrive.

Building on the research by Sousa et al, GIE Foundation analyzes how different ways of altering Somaliland’s status could reduce risks both across migration corridors and for arrivals. We use the movement trajectories not only to highlight Somaliland’s role, but also to assess how the international system currently treats unrecognized but de facto states in contexts where they are needed most. And we ask: If formal recognition is not feasible, are there other ways to empower Somaliland as a stabilizing actor that might be more acceptable internationally.

Displacement in the Somali Network

The work by Sousa et al analyzed migration flows, which were shown not to be randomly dispersed across the country. Instead, they clustered into a dense and asymmetric spatial network, with clear corridors running between the south-central regions and the north and northwest. According to the analysis, these movements can be statistically reconstructed as probabilistic paths across a network of locations, weighted by real-world frequency of movements between regions affected by climate or conflict and settlements. The approach allows researchers to model not only where people could go, but what they are likely to experience along the way.

Each movement event, drawn from verified International Organization for Migration (IOM) tracking data, was broken into a sequence of origin, trajectory, and destination. The research team then used this empirical network to simulate thousands of possible paths; essentially probabilistic journeys made by displaced individuals across the Somali interior. This allows for granular insight into route structure, typical hazard exposure, and geographic convergence zones. It also provides a way to measure risk that is more sensitive than simple distance or origin-destination metrics.

One of the key findings is that displacement routes are consistently shaped by environmental and political factors. The longer a given journey, the more likely it intersects multiple overlapping risks: Conflict zones, drought-affected districts, and regions without access to aid or food assistance. This is not a theoretical correlation, but rather observable in the spatial data: For example, the Sousa et al 2025 study team found that cumulative exposure to hazards including drought, food insecurity and armed clashes, increases proportionally with the number of steps in a trajectory.

Flows of internally displaced persons in the internationally recognized territory of Somalia can be categorized by three conceptual axes:

The southern axis, centered on Mogadishu and the Lower Shabelle region, where displacement is heavily conflict-driven. This is the axis with the most traffic volume.

The central axis, running through the regions of Galguduud and Mudug, with mixed climate and violence triggers. This is the axis with the second highest traffic volume.

The northbound axis, feeding towards Awdal, Woqooyi Galbeed, Togdheer, Sanaag, and Sool – de facto Somaliland territory. This is the axis with the lowest traffic volume.

Path reconstruction and spatial displacement flows. (A) Reconstruction of the path from an origin to a destination point using the displacement matrix. Starting with an origin-destination pair (top panel), running simulations allows us to estimate a potential path between those points (bottom panel). Numbers in the figure correspond to node ID. Such paths enable us to identify the hazards people are likely to encounter if they undertake that journey. (B) Representation of the most probable hazard to occur in each region of Somalia and displacements between regions. The width of the links represents the number of IDPs who took that journey. The southern region exhibits the greatest density of movements, and it is also a region with a high incidence of conflicts.

Source: Walking Through Complex Spatial Patterns of Climate and Conflict-Induced Displacements (Sousa et al, 2025)

Although the northbound axis currently records the lowest displacement volumes, it warrants particular attention because of the structural role Somaliland could play if its institutional capacity were fully recognized. Unlike most Somali regions, Somaliland has sustained relative stability for three decades, maintains functional governance and security institutions, and operates through regular electoral processes. These attributes mean that, in principle, it is better positioned than other parts of internationally-recognized Somalia to serve as a durable endpoint for displaced populations. The paradox is that, despite this potential, the absence of international recognition constrains the territory’s ability to formalize reception, access multilateral finance, or integrate into coordinated humanitarian systems. In other words, by examining the relative paucity of IDP flow to the stable territory of Somaliland, a picture of opportunity loss emerges.

Thus, despite the third axis’s relatively low traffic volume, it is the most relevant to examine for this category. The data shows that a proportion of northbound displacement terminates in or transits through Somaliland. Hargeisa, Berbera, and Burao are likely convergence points in the simulated paths. Displacement tends to reflect the geographic logic of Somali roads, water availability, port access, and relative safety, and is thus purposeful: A UNHCR/JIPS profiling study in Hargeisa explicitly surveyed IDPs from south-central Somalia living in the city; among those groups, “safety/security” was the primary reason for staying in Hargeisa.13 This provides clear evidence of south/central-origin IDPs present in Somaliland’s capital citing stability as the driver.

Yet Somaliland, as a political entity, does not exist in the dataset. It cannot be coded as a distinct endpoint because it does not formally exist in the international system. When displaced people arrive into areas governed by the administration of Somaliland, they are modeled as arriving into the northern zone of Somalia, and as such, they fail to be coded or registered into any sovereign framework capable of receiving, processing, or protecting them under international law. As a result, the most stable node in the Somali displacement network remains disconnected from global protection systems.

This gap has consequences. According to FEWS NET14, the areas receiving the most inbound displacement over this period were also among the least institutionally supported. Hargeisa in particular sits within a region marked according to the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification15 as Stressed (IPC Phase 2) or Crisis (IPC Phase 3), due to pressure from displacement inflows and drought conditions. The same districts that offer relative peace are being stressed by their own inability to integrate arrivals.

Data from ACLED16 reinforces this point. In southern Somalia, displacement often correlates with spikes in organized political violence, particularly in Lower Juba and Banadir districts. In contrast, displacement into Somaliland regions follows drought and localized livelihood collapse as one of the main drivers of displacement. This suggests that Somaliland, even unofficially, is already functioning as a climate displacement sink. But unlike a recognized state, it has no access to multilateral climate finance (though some bilateral climate finance, from the UK) or emergency infrastructure funds. The result is a degradation of local capacity, with no formal channels for relief or adaptation.

Somaliland occupies a latent position in the displacement network. Its districts register IDP arrivals and it hosts south/central-origin IDPs who cite safety as a primary reason to remain in Hargeisa. Yet its role is structurally under-supported: limited access to multilateral finance and formal coordination channels constrains reception, registration, and services. We therefore treat Somaliland as a potential sink (not because Sandro et al’s map encodes edge direction, as it does not), because independent profiling and monitoring show presence and arrivals, and governance indicators point to relative stability. Functionally excluding this node reduces overall system resilience and raises friction – more so given that institutional frameworks to host and serve displaced populations exist but are not fully capitalized.17 Sousa et al’s displacement analysis provides the starting point on which we build conceptual scaffolding to theorize how conditions could be improved if Somaliland had greater legal standing, access to international tools, and authority over its coastal waters. New corridors could be built with reduced hazard exposure. Maritime rescue or food supply chains could terminate in Berbera. None of this is possible in the current regime, not because Somaliland is unstable, but because it is invisible.

Counterfactual Scenarios

The model from Sousa et al treats Somalia’s displacement landscape as a probabilistic flow network, where each node represents a location and each edge represents a recorded flow of people. Transition probabilities between nodes are derived from real displacement data, rather than theoretical assumptions. Within this structure, movement pathways can be reconstructed and analyzed not just as straight-line origin-destination pairs, but as trajectories that pass through multiple hazards. Put simply, the model treats displacement like a network of possible routes, showing how people are likely to move step by step through different places (and hazards) rather than jumping directly from start to finish. Note that the lines in the map do not represent physical routes; they are an artefact of the data visualisation.

In such a network, some nodes act as sources – regions from which displacement originates, often driven by armed conflict or environmental collapse. Others act as sinks – regions where displaced people tend to stop, either because they reach safety, resources, or the end of viable movement routes. A third category includes transit nodes, which channel flows without offering resolution. These are often bottlenecks or chokepoints. Crucially, the functionality of any given node, whether it acts as source, sink, or transit, is not fixed. It depends on time, governance, infrastructure, legal status, and the availability of external support.

Somaliland fits the structural profile of a potential sink. It is relatively secure, institutionally coherent, and geographically positioned to receive northbound flows from the interior. Yet its role in the displacement network is that of a latent node – functionally present, but structurally unsupported. It receives displaced populations, but without the ability to formalize their status, coordinate with external actors, or access the financial tools needed to sustain inflow management. This is not merely a bureaucratic limitation. In network terms, it reduces overall resilience and increases friction across the system. Recognition or structured functional inclusion would increase formal reception and processing in Somaliland.18 Non-recognition blocks ODA/concessional finance and complicates inter-agency coordination, keeping capacity below what the legal/institutional framework could deliver. Removing that constraint would likely increase the share of northbound IDPs who stop and are assisted in Somaliland effectively, rather than stopping in less well-governed areas and thereby increasing a cyclical degradation of capacity in those areas. In short, recognizing and utilizing Somaliland as a sink could improve outcomes and reduce system friction politically, financially, and directly for displaced persons.19

The question becomes: What exactly would change if Somaliland’s status were different?

We can examine this through three counterfactual scenarios, each grounded in plausible modifications to the network’s structural logic. These are rooted in the way the Sousa et al model represents movement probabilities and hazard exposure over time.

Scenario 1: Recognition and Integration into Multilateral Aid Systems

In the first scenario, Somaliland is formally recognized as a sovereign actor. This is a plausible end point since Somaliland largely fulfils the requirements of the 1933 Montevideo Convention on the rights and duties of states. Namely that it has a permanent population, a defined territory - though with some overlapping claims with Puntland - a functioning government whose authority is recognized internally, and a demonstrated capacity to enter into relations with other states.

Recognition would trigger eligibility for international development financing, legal definition of territorial waters, access to climate adaptation funds, and membership in multilateral humanitarian systems. Within the displacement network, this change would reclassify the northern sink region as a fully supported end point.

Under this condition, paths that currently terminate in informal camps or unregulated settlements around Hargeisa or Berbera could instead be routed toward designated reception and integration zones. Transit through hazard-heavy central corridors might also decline if displaced populations viewed the north as a viable legal destination, rather than a dead end, by passing through Ethiopia. As the preliminary research by Sousa et al shows, the presence of a defined terminus reduces exposure to hazards en route and shortens average trajectory length. Fewer steps along the way correspond to lower cumulative exposure to violence, drought, and food insecurity.

Scenario 2: Functional Inclusion in Aid Systems

The second scenario assumes no legal recognition, but a policy shift that treats Somaliland as a distinct actor for operational purposes. This could include bilateral agreements, NGO partnerships, or formal aid corridors routed through Berbera under the auspices of a multilateral partner. In this structure, Somaliland remains unrecognized diplomatically, but receives functionally equivalent treatment in terms of aid delivery, data integration, and migration governance. To illustrate the scale and reality of the problem: In 2016, Somalia received about $1.3 billion in official development assistance, roughly 21 percent of its GDP. Almost all of this was channelled through the federal government in Mogadishu, with almost none reaching Somaliland directly, according to an International Growth Centre report from 201820. This stands to reason; with the Somali and Somaliland administrations at loggerheads, Mogadishu has very few incentives to reduce their own budget by sending aid to Somaliland.

This arrangement resembles how non-state territories are sometimes handled in other contexts the Palestinian Territories, northern Cyprus, or parts of eastern Ukraine prior to full-scale war. In the Somali context, this would allow displacement response actors to explicitly code Somaliland as a terminus in their operational systems. It would also enable hazard mitigation programs, such as targeted food delivery or emergency shelter schemes, to be routed through a coastal point of relative security.

The effect on the displacement network would be modest but measurable. Path lengths would remain similar, but hazard accumulation could be mitigated if arrivals are met with structured response capacity rather than informal settlement. Current IOM data shows that Somaliland and Puntland host tens of thousands of IDPs in substandard conditions. Integrated support could reduce onward displacement, stabilize host communities, and slow the feedback loop between migration and local fragility.

Scenario 3: Maritime Security Coordination Only

The third scenario isolates the security component. Here, Somaliland remains unrecognized, but is integrated into maritime and border security initiatives through informal or indirect means. For example, a Western-led coalition could coordinate naval patrols with Berbera authorities, or fund the training of Somaliland’s coast guard under private security frameworks. This would mirror existing arrangements in Puntland and parts of the Gulf of Guinea.

Such a move would not reclassify Somaliland as a humanitarian endpoint, but would harden the edges and could reduce risk along maritime transit and smuggling corridors. This would limit spillover effects of displacement within Somalia. But as Gao et al. (2025) note, exposure to discrete hazard events often clusters near geographic chokepoints, including port cities, so if Berbera were secured in coordination with international actors, it could reduce risks faced by IDPs along the final steps of northern trajectories. Even modest improvements in maritime security could lower rates of and harms from attempted onward journeys to Yemen or Djibouti.

This scenario does not reshape the displacement network in substance or in major part, but it materially hardens the edges, reducing the cost of instability at key nodes without requiring full legal transformation. For many Western policymakers, this may be the most tractable option in the near term. Recognition is not the only way to resolve the issue; but ignoring Somaliland’s role entirely is no longer a defensible policy position.

Displacement Spillover

Somaliland’s role in the Horn of Africa is not limited to its position within Somalia’s displacement network. It also occupies one of the most sensitive maritime corridors in the world. The port of Berbera sits less than 300 kilometers from the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait; a strategic chokepoint through which nearly 10 percent of global maritime trade flows21. Oil, grain, manufactured goods, and critical minerals pass through this corridor en route to or from the Suez Canal. Any disruption along this route sends ripple effects across global markets.

This proximity has brought both investment and pressure. The United Arab Emirates (UAE), through shipping giant DP World, has invested heavily in Berbera’s port and corridor infrastructure since 2016. UAE interests treat Berbera not just as a trade hub, but as a potential security outpost. Unconfirmed reports have suggested Emirati plans to establish a logistics or naval presence there, though these have not materialized in a formal way. Still, the intent is clear: Berbera matters for control.

Nearly 10 percent of global shipping traffic passes within striking distance of Somaliland’s coast, including oil tankers and container ships en route to or from the Suez Canal. The Port of Berbera’s expansion allows for high-volume trade and provides an alternative to Djibouti for both commercial and security-driven maritime access to East Africa. Unlike Djibouti, where foreign military presence is well established and Chinese investment extensive, from a Western policy perspective, Somaliland offers alignment with Western strategic priorities without great power entanglement.

And for Somaliland itself, recognition is not only about access to aid or strategic value to outside powers. It is about the ability to consolidate its own sovereignty: To trade under its own flag, to access finance directly, and to be treated as a partner rather than an appendage. Recognition would give Somaliland the tools to develop its economy and institutions on its own terms, rather than remaining dependent on intermediaries. Just as importantly, recognition would affirm the national identity that Somalilanders themselves have built over three decades of self-rule. For many, it is not only a matter of diplomacy or economics but of dignity as well; the chance to see their citizenship, institutions, and collective history acknowledged in the international community.

At the same time, the region’s security environment has deteriorated. Houthi missile attacks on Red Sea shipping, launched from Yemen in 2024 and early 2025, prompted naval responses from the U.S., U.K., and European coalitions. Somali piracy has historically imposed a heavy financial and operational cost on both governments and the private sector22. At its height in from 2008-2012, Somali piracy contributed to an estimated global loss of $7 to $12 billion annually, factoring in ransoms, insurance premiums, rerouting, and naval operations23. Most Somali piracy operations during the peak years originated from northeastern and central coastal areas, particularly from Puntland’s ports such as Eyl and Garacad, as well as Hobyo in central Somalia’s Mudug region; these served as central hubs for pirate logistics and operations. The European Union’s Operation Atalanta and the United States-led Combined Task Force 151 invested billions in long-range patrols to protect shipping lanes, often requiring extended deployments and coordination with commercial convoys24. Private security costs soared as well: shipping companies were spending approximately $530 million annually on armed protection for vessels transiting through the region25. For Somalia itself, piracy represented a profound economic, social and governance cost. Revenues from ransom payments accrued to a narrow set of actors, while the wider economy suffered enormous opportunity losses. Coastal fishing communities were destabilised, legitimate maritime trade was diverted away from Somali ports, and the country’s international reputation as a high-risk environment deterred investment. The World Bank has estimated that, while pirate ransoms averaged only about $53 million annually, the Somali economy as a whole lost far more in foregone trade, fisheries, and port revenues.26

By 2024, those costs had risen again, with armed guard fees reaching $20,000 per guard for a three-day Red Sea transit27. Despite a temporary lull, piracy remains a persistent background threat – one that intensifies whenever naval assets are redeployed elsewhere, as seen during escalations of violence by Yemen’s Houthis in 2024–25. And illegal fishing by Chinese and Iranian vessels in Somali and Yemeni waters has reignited coastal grievances, particularly among artisanal fishing communities who see foreign vessels as both economic threat and symbolic violation.

These factors interact directly with displacement patterns. Sousa’s model maps internal displacement flows, showing many routes that end or start in coastal areas. At the same time, maritime migration from Somalia has become a pronounced route of exit. For instance, in 2024, IOM tracked nearly 97,000 migrants from the Horn of Africa (including many Somalis) arriving in Yemen – itself also under significant stress from ongoing unrest – underscoring that maritime transit remains a crucial, albeit perilous, channel28. And it also introduces instability into the littoral areas themselves. Informal camps around Berbera, Zeila, and other coastal towns now house growing numbers of internal migrants and prospective maritime migrants. These settlements are not equipped to process high-throughput movement. While Somaliland security forces maintain a presence in parts of the coast, there is little evidence of sustained mechanisms to screen for or manage trafficking, smuggling, or potential militant infiltration. Although EUCAP Somalia has operated a field office in Hargeisa since 2014,29 providing training and support to the Somaliland Coast Guard in search-and-rescue and maritime law enforcement, these efforts remain modest and localized, and do not equate to a comprehensive, institutionalized presence in informal coastal migration hubs. Somaliland did establish a Maritime Security Coordination Office (MSC Office) in 2023 to oversee maritime security activities, including coordination on trafficking, smuggling, and maritime crime prevention30. However, this office is newly created and its operational capacity remains nascent, making it unlikely to yet provide robust screening infrastructure in the informal settlements around Berbera and Zeila.

This creates a multilayered risk structure:

Local friction as displaced populations stress fragile urban infrastructures.

Transnational security risks as unmanaged flows intersect with illicit maritime networks.

Strategic volatility as global powers compete to anchor influence at the margins of ungoverned space.

In this context, Somaliland’s formal exclusion from maritime security frameworks is more than an institutional omission. It is a vulnerability. The region’s most stable port city is disconnected from both regional coordination bodies and international maritime enforcement platforms. Djibouti, which hosts multiple foreign military facilities, is already saturated. Eritrea remains closed. Yemen is engulfed in conflict. Puntland, while active in anti-piracy efforts, lacks the institutional coherence or diplomatic alignment that Somaliland could potentially offer. There is no other viable partner on the western side of the Bab-el-Mandeb.

If Somaliland were integrated, even informally, into multilateral maritime monitoring systems, several leverage points would emerge: 1) It could serve as a stable logistics hub for anti-smuggling and counter-piracy operations. 2) It could provide a safe port for search-and-rescue missions involving migrant vessels attempting to cross the Gulf of Aden. 3) It could anchor early warning systems for coastal displacement or resource shocks.

Each of these roles corresponds to existing unmet needs. In 2024, the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) noted a sharp uptick in maritime trafficking through the Gulf of Aden. At the same time, IOM reported that more than 70,000 migrants attempted the sea crossing from Somalia to Yemen, despite the war. The combination of displacement and maritime risk is now accumulated instead of sequential. People move north to escape conflict or climate shocks and then face renewed risk at sea.31

This stacking of hazards reflects “pathwise accumulation”: the idea that the further a person moves through a displacement network, the more likely they are to encounter overlapping threats. Movement toward the coast is not an escape from risk; it is often a shift from one domain of instability to another. Recognizing this structure is key to building meaningful interventions.

Yet international responses remain fragmented. Maritime patrols operate under separate mandates from humanitarian agencies. Development finance flows to Mogadishu, despite its limited control of national territory. Displacement monitoring systems continue to treat Somaliland as part of a uniform Somali state, even as it receives distinct inflows and maintains separate institutions.

The current policy architecture relies on a fiction: That the state apparatus of Somalia encompasses its entire territory and can be the sole partner for engagement. In the past, this position may have been defensible as a diplomatic compromise. Today, it imposes operational costs. It prevents resource targeting to where people are actually going. It undermines maritime enforcement by excluding the actor with the most relevant geography. And it increases the risk that coastal displacement turns into transnational crisis.

Recognition is one possible remedy. But even absent recognition, there are potential intermediate solutions: Somaliland could be formally integrated into IOM and UNHCR response frameworks through a geographic exception clause. Bilateral agreements with port states could allow Berbera to function as a designated disembarkation and support point for search-and-rescue operations. A regional maritime coordination cell could be established with technical links to Somaliland authorities, regardless of diplomatic status.

Rethinking Stateless Stability

Each of these scenarios produces different effects on the displacement network, but all illustrate the same underlying point: The current system treats Somaliland as if it were empty space. This assumption is analytically false and operationally dangerous. Sousa et al identify significant displacement flows with nodes in northern Somali districts; while not explicitly labeled as Somaliland, these correspond geographically to Somaliland’s territory, with termination centers at Awdal, Woqooyi Galbeed, Togdheer, Sanaag, and Sool. Yet because that north has no standing in the formal humanitarian system, it cannot function as a stable resolution point; instead migrants cross an internal and unrecognized border. The result is a bottleneck where none needs to exist.

The three scenarios are not radical. They mirror functional workarounds used in other fragile contexts, including Libya, Iraqi Kurdistan, and the Palestinian territories. The precedent exists: The Kurdish Regional Government (KRG) in Iraq, though not an independent state, has long received direct international support: The World Bank, IMF, and bilateral donors channel funds to Erbil for infrastructure, refugee response, and governance programs, and Western militaries coordinate security policy with the Peshmerga32. The Palestinian Authority likewise lacks full UN member-state recognition, yet it is treated as a distinct operational partner: It receives direct budget support from the World Bank and EU, participates in international aid compacts, and is coded separately in humanitarian and displacement data systems33. Both cases show that international institutions can adapt engagement without requiring formal statehood.

What is missing is the political will to acknowledge Somaliland’s operational value – especially in a context where its geography gives it system-level leverage that no other actor in the region possesses. Somaliland’s strategic position – both geographically and institutionally – has made it a recurring topic in discussions of Horn of Africa security. Its relative stability, de facto governance, and port infrastructure make it an obvious candidate for international engagement. Yet, it remains excluded from the major systems that manage displacement, maritime security, and development assistance.

This paper has drawn from recent empirical work on Somali displacement patterns, particularly the study by Sousa et al modeling over 20,000 movement events across the country in early 2025. That data makes two things clear. First, Somaliland is already integrated in the network flow of displaced people moving between Somalia’s central and southern regions. Second, it sits at the edge of a volatile maritime corridor increasingly shaped by overlapping conflict, climate pressure, and migration risk.

In practical terms, Somaliland is absorbing burdens that would normally be managed by formal institutions – without being treated as an institutional actor. It cannot receive development funding through multilateral channels. It is not eligible for security or migration-related coordination mechanisms. It is not integrated into regional maritime response systems. These constraints are a direct result of its political status. They are not the result of its capacity.

We are not arguing that recognition of Somaliland is the only policy response worth considering. That path remains politically complicated and would come with its own risks. In the UK, for example, the issue was debated in the House of Lords in October 2024, with some peers calling for recognition and the government warning that a recent Somaliland–Ethiopia MOU had heightened regional tensions.34

But the current position – treating Somaliland as administratively invisible – is not tenable either. At minimum, policymakers should consider forms of engagement that reflect the functional role Somaliland already plays. That includes:

Coding Somaliland separately in humanitarian and displacement data systems, so that international actors can allocate resources based on actual movement patterns rather than diplomatic cartography.

Establishing formal partnerships with the Port of Berbera and Somaliland’s maritime authorities for logistical support, anti-smuggling coordination, and emergency response.

Developing financing mechanisms that support local governments absorbing regional displacement, regardless of their recognition status. Somaliland is not the only case where this applies, but it is one of the most clear-cut.

Including Somaliland in regional risk assessments and early warning systems, especially those tied to maritime security and coastal displacement. Where the stakes involve international shipping lanes or search-and-rescue operations, there is a compelling argument for pragmatic coordination.

Each of these actions could be pursued without altering formal diplomatic positions. They reflect the kind of functional realism already used in other disputed or semi-recognized territories.

Somaliland is not a perfect partner: It has unresolved internal conflicts, including an armed dispute over the city of Las Anod in eastern Somaliland: In early 2023, local Dhulbahante clan forces declared they would no longer recognise Somaliland’s authority and sought to join Somalia’s federal system. Heavy fighting with Somaliland troops followed, killing hundreds and displacing over 100,000 people into Ethiopia, Puntland, and other parts of Somaliland.

Despite this, no actor in the Horn of Africa offers a combination of port access, political stability, and local legitimacy on remotely similar terms. Ignoring that fact, for the sake of political consistency, introduces unnecessary risk into a region that is already overburdened with it.

The current situation is unsustainable, with a growing share of Somali displacement ending in the north, in a territory that cannot legally or functionally absorb it: In December 2013, Somalia’s total internally displaced population stood at roughly 1.1 million, of which about 84,000 (7%) were in Somaliland, according to a World Bank analysis of UN data. By February 2023, figures from the Protection & Return Monitoring Network (PRMN), cited by Refugees International, put Somaliland’s IDP population at 571,400 out of a national total of approximately 2.57 million – 22% of total and a rise of 15% overall comparatively. This shift indicates a substantial increase in the northern share of displacement over the past decade, supporting the view that Somaliland has absorbed a growing proportion of Somalia’s displaced population (World Bank 2014; Refugees International 2023).

International actors continue to design policies around a Somalia that doesn’t exist in practice. Maritime security operations treat Somaliland’s coastline as a grey zone. Development funding flows into federal channels that cannot reach the north. Meanwhile, the problems – displacement, migration, piracy, smuggling – are increasingly moving toward the areas that the system refuses to acknowledge.

There is a clear rationale for adjustment: The institutions exist and the displacement flows are mapped, creating strong incentives for coordination. In a displacement network, a sink without support becomes a source of new instability. In a maritime corridor, a port without partnership becomes a blind spot. Somaliland is both; it is thus time to stop treating it as an unsightly exception and begin considering its assets and potential place in the international community.

Footnotes

1. Reuters (March 31, 2024): “Somalia's Puntland refuses to recognise federal government after disputed election” — Puntland declared it would “act independently until there is a federal government with a constitution that is agreed upon by a referendum in which Puntland takes part.” https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/somalias-puntland-refuses-recognise-federal-government-after-disputed-2024-03-31/ ↩ Back to text

2. U.S. State Department, 2023 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices – Somalia — recognizes Somaliland’s de facto independence since 1991 https://www.state.gov/reports/2023-country-reports-on-human-rights-practices/somalia/ ↩ Back to text

3. World Bank, Somaliland in Figures (2022). https://www.somalilandcsd.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/A5-CSD_SOMALILAND-IN-FIGURES.pdf ↩ Back to text

4. Freedom House (2024): Confirms Somaliland holds competitive elections, maintains independent security forces, and runs its own judicial system. https://freedomhouse.org/country/somaliland/freedom-world/2024 ↩ Back to text

5. Reuters (December 2024). Coverage of meetings between Turkish President Erdoğan and Somali and Ethiopian leaders states that Somalia is firmly opposed to Somaliland’s independence bid. https://www.reuters.com/world/erdogan-meets-somalia-ethiopia-leaders-separately-amid-somaliland-dispute-2024-12-11/ ↩ Back to text

6. “In 2019 … more than 138,000 Somalis moved to Yemen, and 110,000 arrived in Europe”, Vatican Dicastery for Promoting Integral Human Development, Migrants and Refugees Section. https://migrants-refugees.va/country-profile/somalia/ ↩ Back to text

7. More info here: UNHCR, Somalia Refugee Crisis Explained, UN Refugee Agency. https://www.unrefugees.org/news/somalia-refugee-crisis-explained/ ↩ Back to text

8. More info here: Joint Data Center on Forced Displacement, Somalia Displacement Report, June 2024. https://www.jointdatacenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/Somalia-displacement-report_JUNE2024.pdf ↩ Back to text

9. Mohamed Farah Hersi, State Fragility in Somaliland and Somalia: A Contrast in Peace and State Building (London: International Growth Centre, 2018), 15, https://www.theigc.org/sites/default/files/2018/08/Somaliland-and-Somalia_online.pdf ↩ Back to text

10. More info here: https://www.internal-displacement.org/countries/somalia/ and https://prmn-somalia.unhcr.org/ ↩ Back to text

11. David Carranza, Devansh Sharma, Francisco Malveiro, Gustavo Kohlrausch, Jisha Mariyam John, Kaloyan Danovski, Malvina Bozhidarova, Rui Zheng, Sandro Sousa. “Walking Through Complex Spatial Patterns of Climate and Conflict-Induced Displacements.” arXiv preprint, June 27, 2025. https://arxiv.org/abs/2506.22120. PDF: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2506.22120 ↩ Back to text

12. More info here: UNHRC PRMN: https://prmn-somalia.unhcr.org/ and Norwegian Refugee Council, “Who Are You? Linkages between Legal Identity and Land in Somalia,”— citing UNHCR/PRMN data https://www.nrc.no/globalassets/pdf/reports/who-are-you/full-report_who-are-you_linkages-between-lid-and-hlp-in-somalia.pdf ↩ Back to text

13. Internal displacement profiling in Hargeisa, more information here: https://www.jips.org/uploads/2018/10/Profiling-Report-Somalia-Hargeisa-2015.pdf ↩ Back to text

14. A USAID-funded initiative that monitors and analyzes food security conditions worldwide; it produces regular reports and maps on areas at risk of famine, drought, or food insecurity. More info here: https://fews.net/east-africa/somalia ↩ Back to text

15. The Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC), a globally standardized scale ranging from Phase 1 (Minimal) to Phase 5 (Famine). More info here: https://www.ipcinfo.org/ ↩ Back to text

16. Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project. An independent, non-profit organization specializing in the real-time collection, analysis, and mapping of data on political violence and protest events globally. More info here: https://acleddata.com/ ↩ Back to text

17. More information here: https://freedomhouse.org/country/somaliland/freedom-world/2024 ↩ Back to text

18. State fragility in Somalia vs Somaliland explored here: https://www.theigc.org/sites/default/files/2018/08/Somaliland-and-Somalia_online.pdf ↩ Back to text

19. Peacebuilding without external assistance, Somaliland focus: https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/111428/wp198.pdf ↩ Back to text

20. Report here: https://www.theigc.org/sites/default/files/2018/08/Somaliland-and-Somalia_online.pdf ↩ Back to text

21. Coface (May 2025), a global trade intelligence and insurance organization, estimates that 10–12% of international maritime trade transits the Bab el-Mandeb Strait annually. https://www.coface.ch/news-publications-insights/bab-el-mandeb-strait-tension-at-a-global-trade-route ↩ Back to text

22. More info here: F. Ahmed, “Unravelling the Puzzle of Piracy: A Somali Perspective,” ZEUS Working Paper 6 (2014) https://epub.sub.uni-hamburg.de/epub/volltexte/2014/34309/pdf/ZEUS_Working_Paper_6.pdf ↩ Back to text

23. One Earth Future. The Economic Cost of Somali Piracy 2011. Oceans Beyond Piracy, 2011. https://oneearthfuture.org/research-analysis/economic-cost-somali-piracy-2011. ↩ Back to text

24. European Union Naval Force Somalia. Operation Atalanta Briefings and Factsheets. Accessed July 2025. https://eunavfor.eu. ↩ Back to text

25. World Fishing & Aquaculture. “Illegal Fishing and Coastal Grievances in Somaliland.” World Fishing & Aquaculture, February 2024. https://www.worldfishing.net/news/illegal-fishing-and-coastal-grievances-in-somaliland. ↩ Back to text

26. More info here, from World Bank: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2013/04/11/ending-somali-piracy-will-need-on-shore-solutions-and-international-support-to-rebuild-somalia ↩ Back to text

27. Shabelle Media Network. “Prices for Private Maritime Security Guards Shoot Up after Resurgence of Somali Pirates.” Shabelle Media, April 2024. https://shabellemedia.com/prices-for-private-maritime-security-guards-shoot-up-after-resurgence-of-somali-pirates. ↩ Back to text

28. The IOM’s “Migration Along the Eastern Route” report indicates tracked migrant arrivals in Yemen from the Horn of Africa, including 96,649 in 2023 and 60,897 in 2024. More info here: International Organization for Migration. Migration Along the Eastern Route: Yearly Eastern Route Report 2024. 2025. https://dtm.iom.int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl1461/files/reports/20250212%20IOM%20DTM%20Annual%20Migration%20Report%202024.pdf?iframe=true ↩ Back to text

29. European Union External Action, “‘Maritime Security Has Real Impact’” (EEAS Field Vision, July 4, 2022), on EUCAP Somalia’s operations in Somaliland. https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/fieldvision-%E2%80%98maritime-security-has-real-impact-economic-development-regional-security-and-stability_en ↩ Back to text

30. Republic of Somaliland, Establishment of the Maritime Security Coordination Office of the Republic of Somaliland, April 14, 2023. https://mfa.govsomaliland.org/article/somaliland-maritime-security-coordination-office ↩ Back to text

31. A 2023 Mid-year update reported over 77,000 migrants crossed the Gulf of Aden into Yemen by mid-2023: https://www.iom.int/news/soaring-number-migrants-distress-yemen-demands-greater-relief-efforts ↩ Back to text

32. World Bank. Kurdistan Region of Iraq: Reforming the Economy for Shared Prosperity and Protecting the Vulnerable. Washington, DC: World Bank, 2016. https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/757861468195046060/kurdistan-region-of-iraq-reforming-the-economy-for-shared-prosperity-and-protecting-the-vulnerable ↩ Back to text

33. World Bank. West Bank and Gaza Overview. Washington, DC: World Bank, updated 2024. https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/westbankandgaza/overview ↩ Back to text

34. Read the full debate in the UK House of Lords here: https://hansard.parliament.uk/Lords/2024-10-29/debates/9C63583B-95F5-41AF-AAEE-7EFD667E0945/HornOfAfrica ↩ Back to text

References

Ahmed, F. (2014) Unravelling the Puzzle of Piracy: A Somali Perspective. ZEUS Working Paper 6. [Available here]

Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) (2025) Somalia Dashboard. [Available here]

Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) (n.d.) About ACLED. [Available here]

Carranza, D., Sharma, D., Malveiro, F., Kohlrausch, G., John, J.M., Danovski, K., Bozhidarova, M., Zheng, R. and Sousa, S. (2025) Walking Through Complex Spatial Patterns of Climate and Conflict-Induced Displacements. arXiv preprint. [Available here]

CIA (2025) Somalia. The World Factbook. Page last updated: 20 August 2025. [Available here]

European Union External Action (2022) ‘“Maritime Security Has Real Impact” (EEAS Field Vision, July 4, 2022) on EUCAP Somalia’s operations in Somaliland’. [Available here]

European Union Naval Force Somalia (2025) Operation Atalanta Briefings and Factsheets. [Available here]

Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET) (2024–2025) East Africa Food Security Outlook Reports: Somalia. USAID. [Available here]

Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET) (n.d.) East Africa: Somalia. [Available here]

Foreign Policy (2024) ‘Strategic Maritime Chokepoints and Regional Powers’. Foreign Policy, 4 November. [Available here]

Freedom House (2024) Somaliland. Freedom in the World 2024. Washington, DC: Freedom House. [Available here]

Hersi, M.F. (2018) State Fragility in Somaliland and Somalia: A Contrast in Peace and State Building. London: International Growth Centre, LSE–Oxford Commission on State Fragility, Growth and Development. [Available here]

Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC) (n.d.) Somalia: Internal Displacement. Geneva: IDMC. [Available here]

International Organization for Migration (IOM) (2024–2025) Displacement Tracking Matrix: Somalia Reports. [Available here]

International Organization for Migration (IOM) (2024–2025) Horn of Africa to Yemen: Regional Migrant Response Plan. [Available here]

International Organization for Migration (IOM) (2025) Migration Along the Eastern Route: Yearly Eastern Route Report 2024. [Available here]

IPC Global Partnership (n.d.) About the IPC: Overview and Classification System. [Available here]

Joint Data Center on Forced Displacement (2024) Somalia Displacement Report, June 2024. [Available here]

Migrants & Refugees Section (2025) Country Profile: Somalia. Dicastery for Promoting Integral Human Development, Vatican. [Available here]

Modern Diplomacy (2024) ‘A Legal and Diplomatic Analysis of Somaliland’s Quest for International Recognition’. Modern Diplomacy, 19 March. [Available here]

Norwegian Refugee Council (2021) Who Are You? Linkages between Legal Identity and Land in Somalia. Oslo: NRC. [Available here]

One Earth Future (2011) The Economic Cost of Somali Piracy 2011. Oceans Beyond Piracy. [Available here]

Refugees International (2023) No Going Back: The New Urban Face of Internal Displacement in Somalia. Washington, DC: Refugees International. [Available here]

Republic of Somaliland (2023) Establishment of the Maritime Security Coordination Office of the Republic of Somaliland, 14 April. [Available here]

Reuters (2024a) ‘Somalia’s Puntland Refuses to Recognise Federal Government after Disputed Election’. Reuters, 31 March. [Available here]

Reuters (2024b) ‘Erdogan Meets Somalia, Ethiopia Leaders Separately amid Somaliland Dispute’. Reuters, 11 December. [Available here]

Shabelle Media Network (2024) ‘Prices for Private Maritime Security Guards Shoot Up after Resurgence of Somali Pirates’. Shabelle Media, April. [Available here]

United Kingdom. House of Lords (2024) Horn of Africa, debate, 29 October 2024. Lords Hansard. [Available here]

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) (2025) Somalia Refugee Crisis Explained. [Available here]

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) (2025) Protection & Return Monitoring Network (PRMN) Dashboard. UNHCR Somalia Data Portal. [Available here]

United States Department of State (2023) 2023 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices: Somalia. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of State. [Available here]

World Bank (2013) The Pirates of Somalia: Ending the Threat, Rebuilding a Nation. Washington, DC: World Bank. [Available here]

World Bank (2014) Analysis of Displacement in Somalia. Washington, DC: World Bank. [Available here]

World Bank (2016) Kurdistan Region of Iraq: Reforming the Economy for Shared Prosperity and Protecting the Vulnerable. Washington, DC: World Bank. [Available here]

World Bank (2022) Somaliland in Figures. Washington, DC: World Bank. [Available here]

World Bank (2024) West Bank and Gaza Overview. Washington, DC: World Bank. [Available here]

World Fishing & Aquaculture (2024) ‘Illegal Fishing and Coastal Grievances in Somaliland.’ World Fishing & Aquaculture, February. [Available here]

International Organization for Migration (IOM). (2023). Soaring number of migrants in distress in Yemen demands greater relief efforts. [Available here]

Eubank, N. (2010). Peace-Building without External Assistance: Lessons from Somaliland. CGD Working Paper 198, Washington, D.C.: Center for Global Development. [Available here]

Hersi, M.F. (2018). State fragility in Somaliland and Somalia: A contrast in peace and state building. (International Growth Centre/LSE-Oxford Commission on State Fragility report). [Available here]

Joint IDP Profiling Service (JIPS); UNHCR. (2015). Internal Displacement Profiling in Hargeisa. December 2015. [Available here]

Freedom House. (2024). Freedom in the World 2024: Somaliland. [Available here]

Mosley, J. (2015) Somalia’s Federal Future: Layered Agendas, Risks and Opportunities. Chatham House Research Paper, Africa Programme, September. [Available here]

Featured Image Credit: NASA/METI/AIST/Japan Space Systems, and U.S./Japan ASTER Science Team, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons