The Atlantic Divide on Parking Reform

Europe is Outpacing North America in Reconciling the Automobile with Sustainable, Liveable Cities

By Nick Rowcliffe

When US academic and parking policy specialist Donald Shoup died in February of 2025, he was widely mourned in urban and transport planning circles [1]. One article dubbed him “The prophet of parking” [2]. Shoup spent decades, mainly at the University of California at Los Angeles, focusing single-mindedly on making the case for parking reform. He became better known in his later years, sparking a vibrant international network of advocates for his ideas.

Shoup’s essential insight was encapsulated in the title of his 2005 book “The High Cost of Free Parking”. In this, he argued that parking provision is too often forced into over-supply through legal requirements on landowners to make extensive provision for it. He argued that this brings deleterious consequences for the towns and cities where most people live, by allocating scarce and expensive space to vehicle parking rather than other things, irrespective of demand, raising costs of competing land uses and effectively subsidizing driving compared with other transport modes [3].

At the core of Shoup’s work was his attempt to reverse decades of requirements for private developers to provide minimum levels of off-street parking, and in so doing, to rebalance the use of space in towns and cities.

Beginning with Shoup and expanding to encompass other parking reform theories and ideas, GIE Foundation is examining parking reform as part of a wider effort to understand how infrastructure policy choices shape economic efficiency, sustainability, and urban well-being. This commentary looks at the contrasting trajectories on either side of the Atlantic, asking why Europe has moved more decisively than North America to scale back parking minimums, and what that reveals about governance, planning cultures, and the politics of land use.

For policymakers, the lesson is that small, seemingly technical rules - like parking minimums - carry outsized consequences for how cities grow, how people move, and how sustainable our communities can become. Europe’s willingness to revisit and roll back entrenched rules shows that reform is possible, but only when political systems are able to challenge decades of inertia. North America’s slower progress is a reminder that the cost of inaction is not abstract: It is paid daily in congestion, housing shortages, higher emissions, and cities that serve cars more than people.

A Brief History of Parking Mandates

Parking minimums - or mandates - for residential, retail and other developments began appearing in both North America and Europe even before the Second World War in response to street congestion. They proliferated across both continents in the post-war period, reaching a maximum around the 1970s and thereafter remaining largely in place for decades.

In North America, Edmonton, in Alberta, Canada, was a typical example. The requirement here was for one parking space per residential dwelling. For apartment blocks, the requirement was instead 1.1 spaces per dwelling. Retail establishments were required to provide one space per 20 square metres of shop area; restaurants to provide one space per three seats, and hotels one space per guest room [4].

Specific rules varied by town, city and state. For example, Buffalo in New York required even more residential parking provision, at 1.5 spaces per dwelling of any kind. Hotels were required to provide one space per guest room, plus one per employee and one per conference room. On the other hand, the city had a slightly lighter retail requirement of one space per 28 square metres of shop area. But it also applied rules to offices, which were required to provide one space per 23 square metres of usable floor space [5].

Rules covered a myriad of other types of developments. Houston, Texas, required bars and nightclubs to provide one parking space per 9 square metres of floor space. Los Angeles, California imposed a similar requirement on restaurants. Los Angeles also required schools to provide one space per employee plus one per 10 students; and universities to provide up to one space per three students. Phoenix, Arizona mandated places of worship to provide one space per four fixed seats. Chicago, Illinois required one space per 4.6 metres of floor space at funeral homes. Fremont, California demanded one space per four burial plots at cemeteries.

Residential off-street parking minimums became common across European countries too, though with great variation. A survey of 12 mid-sized cities in Germany, Netherlands and Switzerland published as recently as 2024 found that every single one had residential parking minimums in force [6].

Parking minimums for non-residential developments were also introduced in Europe, though less frequently than in North America and less onerous. Dutch cities including Amsterdam and Utrecht used to have parking norms for non-residential uses including offices, schools and retail. Regulations passed in Malaga, Spain as recently as 2010, require 1 parking space per 50 square metres of retail space. Vienna, Austria has a 2008 “garage law” requiring hotels to provide one parking space per 5 rooms, 1 space per 100 square metres of space in schools and hospitals, and 1 space per 50 visitors to sports stadiums [7].

For policymakers, the historical record is a reminder that regulatory defaults rarely remain neutral. Once embedded, rules like parking mandates accumulate hidden economic and social costs for decades. Reform requires political courage, precisely because the problem is not obvious until the cumulative burden becomes inescapable.

The High Cost of Free Parking

As Donald Shoup and others documented over decades, such widespread requirements for automobile parking had big impacts on the look and feel of urban areas and on travel patterns, particularly in North America. It has been estimated that 39% of the land area of the central business district of Jackson, Wyoming, is assigned to parking, and 26% of the downtown part of both Atlanta, Georgia and Houston, Texas [8].

Map of parking lots in downtown Atlanta Georgia. Source: Parking Reform Network [9].

Providing this parking capacity carries significant direct costs. In a U.S. context, delivering a single surface parking space has been priced at US$5,000-US$10,000 [10], and an underground parking space at up to US$60,000 [11].

The opportunity costs of enforced parking provision are far larger, starting with less space being available for other things, including housing. If supply of a good is constrained, its price goes up. A 2016 study in Los Angeles found that each off-street parking space was adding around US$1,700 per year to apartment rent levels [12]. Another study in Oakland, California found that each mandated residential parking space increased housing construction costs by nearly US$36,000 per unit [13].

Researchers found that parking mandates in Los Angeles, California had reduced the potential number of new residential developments per site by up to 13%. In San Diego, California the feasibility of developing affordable housing units was estimated to be reduced by up to 25% [14]. Returning to Los Angeles, a 2018 report found that land used for parking had an aggregate opportunity cost of US$200 million per year in foregone commercial development or housing value.

As well as increasing costs of other land uses, parking mandates encourage and then lock-in demand for driving as a primary mode of transport, making development of public transit more difficult and compromising walkability. A 2020 study across US downtowns found that a high parking-to-building ratio strongly correlated with lower levels of walking or mass transit usage. One of Donald Shoup’s more arresting assertions was that in some areas of Los Angeles, cruising to find a parking space accounted for 30% of downtown traffic. Just as with road space, more parking capacity, induces demand for more driving [15].

High levels of automobile use in urban areas produces environmental harms, including more congestion, more air pollution and more greenhouse gas emissions. In 2010 the Transportation Research Board, a U.S. organization, estimated that for every 1,000 parking spaces, annual CO2 emissions increase by 300-400 metric tonnes. Another study found that in just one Los Angeles district, cruising for parking produced 1.53 million excess vehicle miles in a year—emitting about 660 metric tonnes of carbon dioxide [16].

Paved surface parking can also exacerbate local water pollution and urban heat island effects. According to one estimate, a typical 4 hectare surface car park produces 1 million litres of stormwater runoff per 2.5cm rain event, potentially carrying oil, heavy metals and other pollutants into waterways [17]. Surface parking can raise urban temperatures by up to 10 degrees compared with vegetated areas.

Unused parking in a light industrial area near Durham, North Carolina. Source: CityBuilder [18].

All kinds of urban residents and visitors pay the costs of excessive parking provision, but in particular those who don’t own a vehicle, who face extra housing costs and reduced walkability or access to mass transit options for no benefits. This group tends to include the poorest in society.

Thus, at the policy level, the trade off should be made clear and explicit: Parking mandates are not free infrastructure. They function as a stealth tax on housing, a subsidy to driving, and a liability for climate and public health goals. Governments that leave such rules untouched are actively choosing higher rents, higher emissions, and weaker alternatives to the car.

Shoup’s Three-Legged Stool

Shoup’s work outlined several policy steps to mitigate the negative externalities of excessive parking provision. His research focused on how urban parking can be considered a public good, to be priced and managed in a way that achieves a good balance between the many conflicting needs of healthy, vibrant and liveable urban areas. Shoup explored many specific parking policy options. But, as set out in his 2018 follow-up book Parking and the City, he put most emphasis on three key changes [3].

The first was to remove all requirements for off-street parking on private land (parking mandates). Shoup argued that developers and businesses should be able to decide how many parking spaces to provide for their customers, rather than being subjected to mandatory minimums.

The second was to introduce demand-based pricing for public parking, on-street and in car parks. As with private off-street parking, allocating curb-side space to parking, as well as municipal off-street parking, is not cost-free, and generates many of the same negative externalities as discussed above for parking mandates. Shoup argued that curbside and municipal parking lot prices should be set based on demand, targeting keeping one or two open spaces per block at all times. He calculated an ideal occupancy rate to be about 85% and advocated for dynamic pricing regimes that would target that level.

The third was to recycle municipal car parking charge revenues locally, through what Shoup called “Parking Benefit Districts”. Shoup saw that public perceptions of curbside parking spaces in particular as being “free” were a big political barrier to right-pricing. His answer was to hypothecate revenues from public parking back into the local area to fund local public services such as sidewalk repairs, street cleaning, or new trees. His aim was to make demand-based parking prices politically popular by allowing local stakeholders to see their meter money at work through visible improvements like sidewalk repairs, street cleaning, or new trees.

Given Shoup’s influence on parking reform internationally, it is interesting to review how far his three-legged stool of policy options has been taken up in North America and Europe.

Donald Shoup, parking reform “guru”. Source: UCLA [19].

Parking Reforms in North America

Donald Shoup’s recommendations took many years to win favor among planners in North America, but by the 2010s a growing number of academics began building on his insights through research, case studies and policy advocacy. In the last decade this led to an acceleration in town, city and state or province-wide parking reforms.

Some notable and trailblazer examples include:

Minneapolis, Minnesota became the first city to begin implementing Donald Shoup’s ideas. This began in 2009 followed by successive waves of deeper change. Initially, parking minimums were eliminated just in the downtown area. In 2015 residential parking minimums were repealed near high-speed transit and reduced by 10% near standard transit [20]. After further changes in 2016 and 2017, and along with the neighboring city of St Paul, Minneapolis removed all off-street parking minimums across all land uses, citywide, in 2021.

In 2017, Buffalo became the first US city to remove parking minimums city-wide across all land uses under its Green Code. This also required major developments to produce a “transportation demand management” plan, and shifted from use-based zoning to a form-based code, prioritizing urban form (e.g., building placement, street engagement) over prescriptive parking rules.

In 2018, San Francisco, California eliminated off-street parking minimums for all land uses except mortuaries and converted what had been minimum requirements for parking spaces into maximums. For example, for residential developments, a parking minimum of up to one space per unit was replaced by a parking maximum of up to one space per unit [21].

In 2022 California and Oregon became the first US states to pass state-wide parking reforms. Both of these banned off-street parking minimums for commercial and residential developments in metropolitan areas within half a mile of frequent public transit.

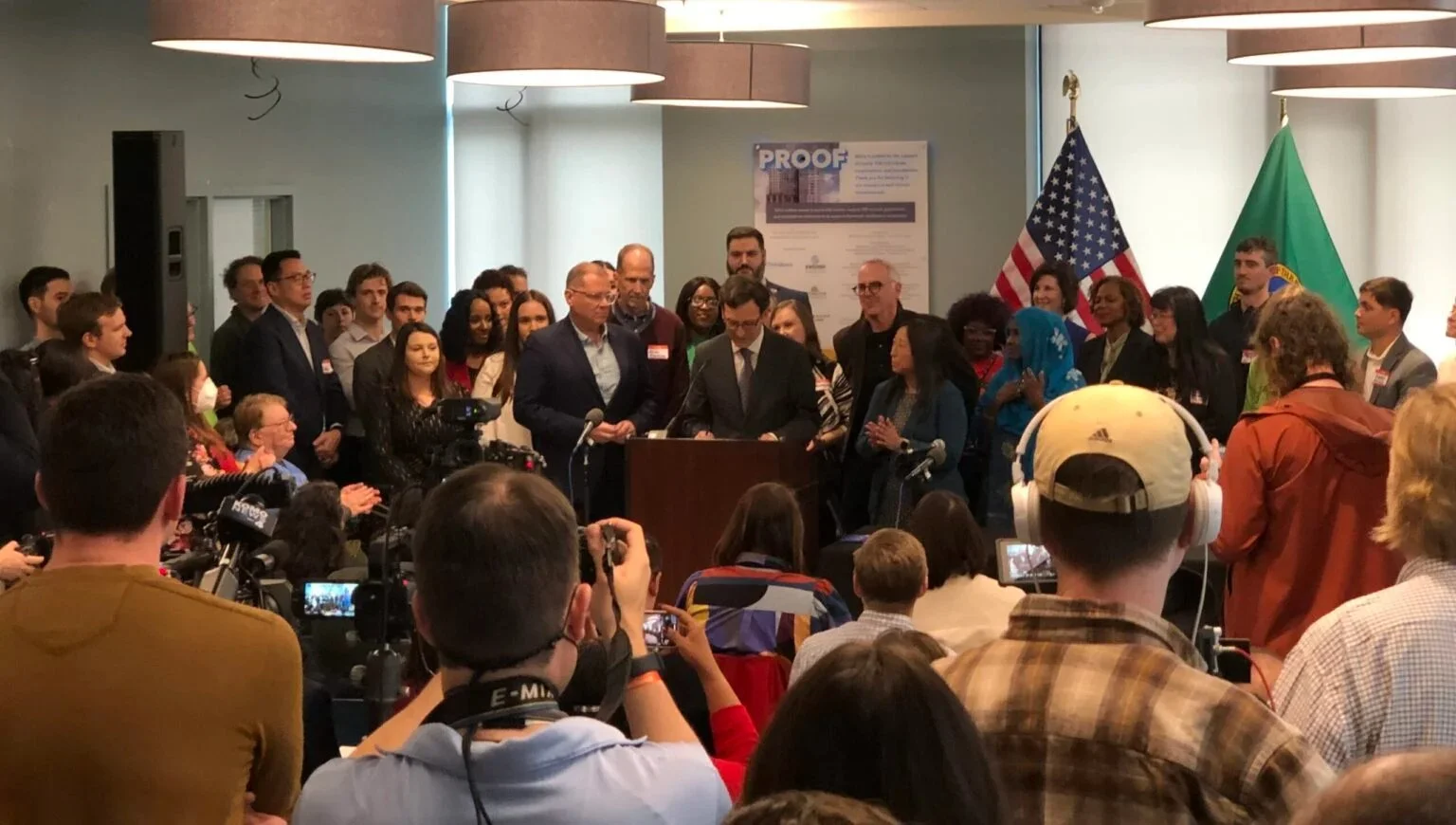

In 2025, Washington introduced what has been cited as the deepest state-wide parking reform yet. Its Parking Reform and Modernization Act SB 5184 applies to all communities above 30,000 population, is not limited to transit corridors, and applies to all land uses and geographies. For a wide range of land uses, local governments may not require parking provision at all. These include housing units under 1,200 sq ft, commercial buildings under 3,000 sq ft, affordable housing, child care center, and reuse of existing buildings through redevelopment. For other specified uses, the Act permits parking minimums, but only up to quite restrictive caps: no more than 0.5 spaces per unit of multi-family housing, and no more than 2 spaces per 1,000 sq ft of commercial development [22].

Washington state Governor Ferguson signs the 2025 Parking Reform and Modernization Act. Source: Sightline Institute [22].

Other notable examples over the past ten years include Houston, Texas, in 2019; the cities of Edmonton and Toronto in Canada in 2020 and 2021; and the California Bay Area cities of San Diego, Alameda, Berkeley, Emeryville, Culver City, San Jose, Mountain View, and Sacramento in 2021. The state of Colorado passed a parking reform in 2022. And in June 2025 North Carolina passed a Parking Lot Reform Act, HB 369, banning local off-street parking minimums and allowing for enhanced controls on stormwater runoff for parking areas being redeveloped.

Moreover, the pace of change is accelerating, with potential parking reforms under discussion as of mid-2025 in Denver, Colorado, and in the states of Connecticut, New Hampshire, Minnesota and Florida.

Parking reforms haven’t been successful everywhere in North America; Miami being the highest profile example of a reform being introduced, then reversed. However, the vast majority of policies have been retained, and implementing cities and states tend to report significant benefits. Following reform in Buffalo, new major projects added 21% fewer parking spaces, generating an estimated US$30 million in savings. In the first two years following the reform, 68% of new housing units built would have been illegal under old rules [23].

In the eight years after Seattle, WA eliminated residential off-street parking minimums in transit corridors, 868 residential projects were built in reform zones, providing 40% fewer parking spaces than previously would have been required. This was estimated to have saved US$537 million in construction costs and freed up 58 hectares for other uses [24].

While statistical studies of impacts on rental or housing costs following introduction of parking reforms appear to be elusive, there is a great deal of circumstantial evidence that they have helped. After it implemented reforms in 2017, for example, Hartford, Connecticut reported an increase in housing supply and reduced rental costs [25].

Parking Reforms in Europe

Parking has been just as hot a political topic in Europe as in North America, and the continent has seen its own wave of parking reforms, but with distinct features, driven by different history, geography and politics.

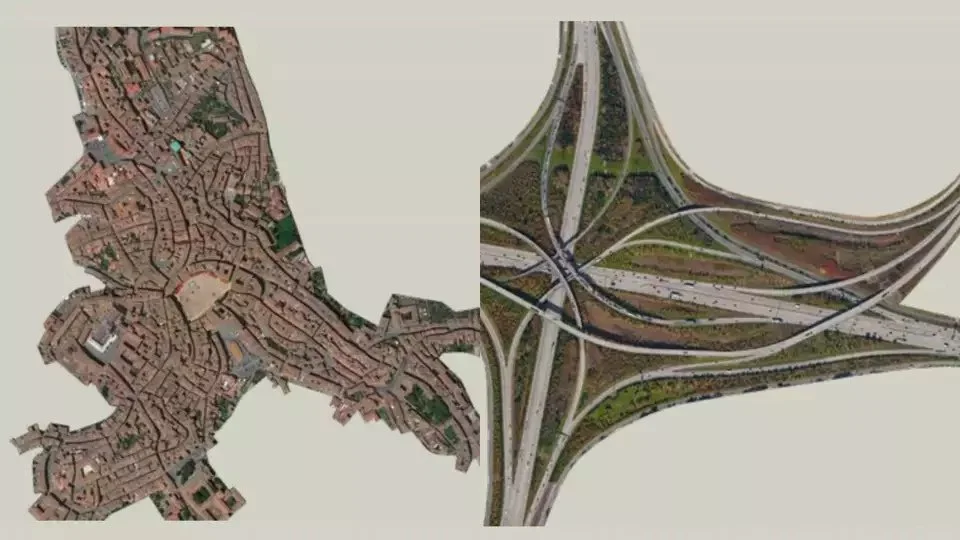

An image that went viral in 2020 showing the centre of Siena, Italy home to 30,000 people, and, at the same scale, a highway intersection in Houston, TX. Source: Chron [26].

A study published in 2011 warned that: “Progress in Europe on parking reform should not be overstated”, pointing out that “Most cities still impose minimum parking requirements on developers, and few cities have imposed maximum parking requirements.” It added that: “While a growing number of cities have mandated charges for both on- and off-street parking, they generally charge rates that are too low” [27].

Yet in several respects this underplays the differences between North America and Europe, at least between trailblazer cities. For a start, modern parking reforms began a lot earlier in Europe than in North America. As early as 1976, London, UK introduced parking maximums (not minimums) for offices and shops in its downtown area. In 1994 a widely cited reform in Zürich, Switzerland, introduced a cap on overall parking capacity by matching any new off-street spaces with removal of on-street capacity. Berlin, Germany became the first city to drop off-street parking mandates city-wide in 1997 [28].

Since the 1990s parking reforms have grown in number and scale across European cities. These include many more sophisticated parking management approaches, including higher pricing and stricter enforcement. But European reforms have also gone well beyond measures advocated by Donald Shoup or commonly implemented in North America, to embrace wholesale parking restrictionism.

Restrictions on private off-street parking are becoming more common. Since the 2004 London Plan, parking maximums have been imposed in the UK capital on most new private developments, particularly near public transit. For example, residential developments in central areas may be permitted as few as 0.1 spaces per unit [29]. Since the 1990s, Vienna, Austria has promoted car-free housing developments, such as the “Wohnprojekt Wien,” where developers commit to no parking at all, and residents pledge not to own cars [30]. In Amsterdam, strict parking maximums are enforced, and in some areas, new developments must include zero parking [31]. In Freiburg, Germany, the Vauban district has been a global model of car-lite development: no private parking is provided on-site unless purchased separately in a shared structure, located outside the neighborhood [32].

A second tactic in growing use in Europe is the targeted removal of on-street parking. Paris, France, is a leader in this regard, currently in process of removing 50% of on-street parking spaces - some 70,000 in total, with the objective of allocating space instead to social uses, trees and cycle lanes [33]. A growing number of cities have reallocated road space aggressively to cycling. For example, London’s strategic cycling network is now longer than the tube network, and the number of cycling journeys increased by over a quarter between 2019 and 2024 [34].

In Barcelona, Spain, under the “Superblocks” model, car access and parking are heavily restricted within clusters of city blocks, effectively banning parking [35]. Oslo, Norway removed almost all on-street parking in its central core in 2019, replaced with bike lanes and green space. Car access is permitted only under narrow conditions, such as for delivery [36].

Some cities have gone even further, by suppressing driving too. Reforms in Barcelona and Oslo not only restrict parking but also through traffic, creating so-called low-traffic zones in which demand for parking will naturally be lower. London’s congestion charge zone, low-emissions zones and low-traffic neighborhoods discourage driving through high charges and limited access. In Brussels, Belgium, the Good Move plan includes a city-wide traffic circulation plan to filter out through traffic from residential streets, combined with parking limits [37].

Other approaches are also being taken across Europe. Especially in Germany, Netherlands, Belgium and across Scandinavia, cities are limiting residential parking permits per household and restricting non-resident parking. Another notable policy is park-and-ride combining out-of-city parking lots with rapid transit into downtown areas. Schemes like these can be found in Zurich, Switzerland; Vienna, Austria; and Oxford, UK.

Assessing Shoup’s Legacy

Relating all these reforms across both North America and Europe back to Donald Shoup’s three-legged stool of parking reforms reveals several clear features.

The first is that parking minimums are increasingly being removed, in line with Shoup’s recommendation, and these reforms are becoming permanent as evidence of benefits in terms of increased housing provision, lower housing rents and so on becomes clearer. Another factor that has assisted is that removing parking minimums does not add costs to local government budgets. The age of parking minimums on private developments is definitely now on the wane across North America and Europe, and Shoup helped kick-start this trend.

On the other hand, take-up of Shoup’s other two key policy recommendations has been significantly lower.

There are instances of dynamic market pricing of on-street parking, of which the SFPark scheme in San Francisco, California, is the most prominent. Calgary, Alberta introduced a similar scheme in 2008. Seattle has flexible pricing just for downtown curbside parking, and Los Angeles has experimented with dynamic pricing, but not implemented it broadly. In Europe too, dynamic pricing is not unknown. Madrid, Spain, pioneered dynamic curb pricing in 2014, adjusting rates based on vehicle type and occupancy, for example 20% lower when under 30% full, and 20% higher when 65-85% full. The first dynamic pricing for municipal garages was introduced in Germany in 2019, initially in Hamburg, Stuttgart and Dresden, later expanded to Frankfurt, Berlin, Cologne the same year.

However, these examples remain outliers, with most cities sticking with fixed parking prices for a number of reasons. A chief one is complexity: dynamic pricing requires greater engagement by local government, including up-front investment, and potentially fiscal risk. Implementation can be operationally challenging and many municipalities have lacked the data systems or capacity to manage price changes. Dynamic pricing can also be resisted by voters, small businesses and car-owning residents.

Parking Benefit Districts remain even less implemented, though again with some exceptions. The most well known is Pasadena, California. Here, a scheme was introduced as early as 1993, based partly on personal advice from Donald Shoup, and remains in force today. Aimed at tackling blight, disinvestment and parking congestion, parking meters were introduced in Old Pasadena, charging market rates, with three-quarters of revenues earmarked for reinvestment in the district and one quarter to a citywide general fund. The main ways revenues are reinvested locally are sidewalk cleaning and repairs, historic lighting, street furniture and landscaping, and security and pedestrian improvements. Pasadena was able to borrow US$5 million against future meter revenue to finance an initial program of environmental improvements. Pasadena’s Parking Benefit District became locally popular [38].

A few other North American cities have followed suit: Austin, Texas, St Louis; Ventura, California; and Washington, D.C. all earmark revenue from curb parking to pay for public services in the metered districts. The last of these returns 75% of meter revenues around the Nationals Park sports stadium to the metered neighborhood to make non-automobile transportation improvements [39].

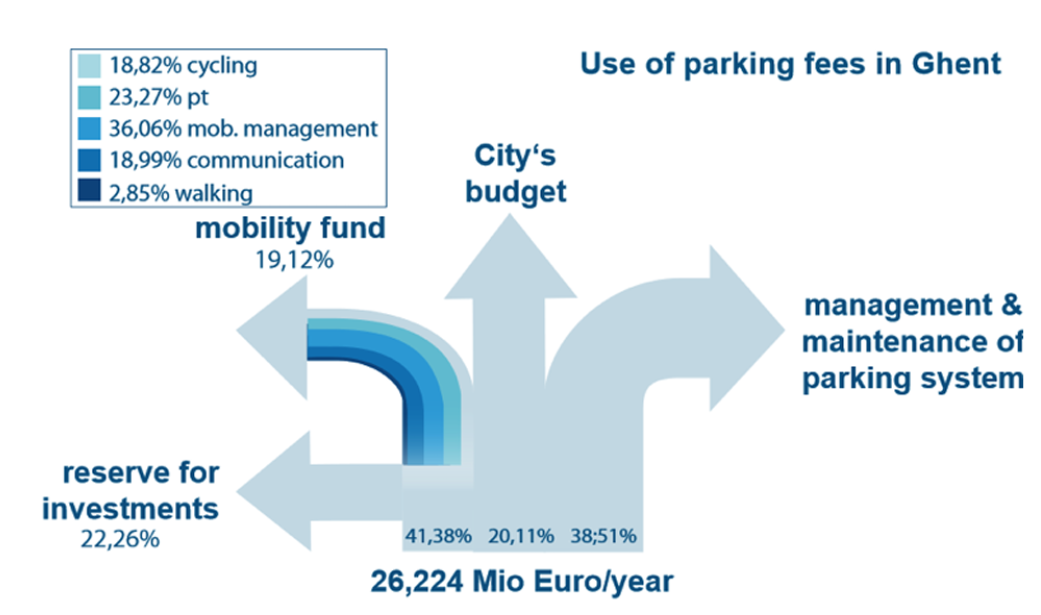

Only a few European cities have introduced a variant of Parking Benefit Districts, in the form of earmarking of parking revenues to be spent on alternative, more sustainable transport modes. Ghent, Belgium, for example, allocates 19% of parking revenues to a mobility fund aimed at improving access to and take up of cycling and walking.

Nearly one-fifth of parking fees in Ghent, Belgium, are earmarked for spending on active travel. Source: European Commission [40].

As with dynamic pricing of public parking, complexity and politics appear to be critical factors in the limited take-up of Parking Benefit Districts. As well as the difficulty of winning over local businesses and drivers, they can challenge established approaches to municipal finances. In many cities, parking revenue goes into general funds and is used for diverse purposes. Earmarking it for specific neighborhoods can upset existing fiscal planning and cross-subsidies. Perceived unfairness of some areas receiving additional funding for local improvements while others don’t can also be a political barrier to implementation. So too is the convenience of driving in many circumstances a higher barrier to implementation than even political will, though the complex factors that create the perception and reality of the convenience of driving are beyond the scope of parking reform.

A recent article highlights some of the practical challenges with reference to Richmond, Virginia, where a Parking Benefit District was proposed but did not progress. In the author’s view: “Many business owners don’t want their customers to pay for parking, and customers don’t want to pay either if the benefits of paying aren’t felt. The idea that meter revenue could go directly into street improvements - making the area cleaner, greener, and more attractive - just doesn’t seem to break through. Even if that money would more than make up for the inconvenience, and even if it meant relying less on city grants and top-ups, the message hasn’t landed” [41].

The lesson is that technocratic reforms succeed only when they are matched with political strategies that make the benefits tangible. Europe’s progress shows that pairing restrictions with visible reinvestment and broader climate or health goals can build coalitions for change. North America’s patchier record illustrates the cost of failing to link reforms to a wider political narrative.

Going Beyond Shoup

The other main observation from parking reform trends is how far some cities, particularly in Europe, have gone beyond Shoup’s three-legged stool. Shoup argued that his ideas should be attractive right across the political spectrum, including free marketeers, socialists, environmentalists and planners. But with hindsight it is clear that his philosophy was of its time and place.

Whereas Shoup’s menu of key policies is based primarily on using market mechanisms to get the right balance between parking and other uses for valuable urban land, cities are increasingly using planning and other administrative approaches, such as travel demand management (TDM) policies, often including goals of shifting journeys away from automobiles to transit and active travel, including by restricting or even eliminating access to parking.

This trend is particularly apparent in Europe, where a much stronger framework of European Union and national laws on transport, planning and land use have required or created space for municipal parking reforms. EU policies such as the Green Deal and air quality directives have acted as indirect levers. In France, a national mobility law passed in 2019 specifically mandates local mobility plans and encourages curbside pricing reform and public space reallocation. Likewise, in the Netherlands national guidance on integrated transport-land use planning supports cities in using pricing, permits, and spatial restrictions.

There has also been a stronger political focus in Europe on tackling climate change by achieving radical reductions in greenhouse gas emissions, as well as on bringing down urban air pollution. Thirdly, there is a stronger emphasis on public health, embracing not only cleaner air but also tackling issues like obesity linked to sedentary lifestyles. Finally, equity-based arguments for equal access to urban transport have been more influential in Europe.

Donald Shoup’s ideas reshaped the way we understand parking, but the reforms now underway in Europe show that his three-legged stool was only the beginning. There’s now a strong consensus across both continents that parking mandates should be removed, though even on this basic step Europe has moved faster than North America. Dynamic pricing for on-street parking, and especially local reinvestment of parking revenues remain relatively unexplored options in either continent, showing the limits of market mechanisms in highly contested local political environments. Meanwhile, Europe is setting the agenda with parking reforms, including administrative parking restrictionism, aimed at actively shifting travel behaviors away from the private automobile.

Thus, for legislators, four priorities should stand out as lessons from Shoup’s proposals and the comparative examples of actual parking reforms found across North America and Europe:

Limit parking capacity. Stop mandating excess parking and, where appropriate, cap provision instead to free up land for housing, commerce, and public space.

Price transparently. Treat curb and lot parking spaces as a scarce resource, use demand-based pricing where feasible, and make costs visible rather than hidden.

Reinvest visibly. Dedicate a share of revenues or savings to local improvements - housing, transit, green space - so communities see direct returns from reform.

Reduce demand. The most powerful lever in some respects, exemplified by a number of European cities, is to reduce demand for parking by facilitating and encouraging alternative travel modes - convenient transit, safe cycling and walkable streets.

Parking reform is no longer a niche urbanist concern but a driver for economic growth, urban vitality, social inclusion, and environmental improvement. The lesson from Europe is not just that historic pro-parking rules can be rolled back, but that cities can actively design their streets around wider goals than just the automobile. Reform means moving from minimums to maximums, from mandates to choice, and from hidden subsidies to transparent trade-offs. Above all, it means recognizing parking policy as economic policy: a choice about whether scarce urban land is treated as a sunk cost for cars, or as an asset to unlock housing, productivity, and cleaner growth.

References

1. Donald Shoup, a Parking Guru Who Reshaped the Urban Landscape, Dies at 86, John Mooallem, Wall Street Journal. (2025). [Available here]

2. The prophet of parking: a eulogy for the great Donald Shoup, M. Nolan Gray, Works in Progress. (2025). [Available here]

3. Links to published works by Donald Shoup, including The high cost of free parking (2005), and Parking and the city (2018). [Available here]

4. History of Parking Requirements, City of Edmonton (2020). [Available here]

5. Buffalo Green Code: Unified development ordinance overview. City of Buffalo. (2017). [Available here]

6. The adequacy of residential parking requirements: a comparison of demand and required supply in European cities, Laura Merten & Tobias Kuhnimhof, European Transport Research Review. (2024). [Available here]

7. Stellplatsverpflichtung (Parking space obligations information sheet), Wirtschaftskammer Wien (Vienna Chamber of Commerce). [Available here]

8. More than one quarter of downtown Houston is dedicated to parking, Houston Chronicle. (2023). [Available here]

9. Parking Lot Map, Parking Reform Network. [Available here]

10. The price of parking, Joe Cortright, City Observatory. (2016). [Available here]

11. Parking reform in Washington, parking reform everywhere, Volts podcast. (2025). [Available here]

12. What Mandatory Parking Requirements Cost L.A. Renters, Joe Linton, L.A. Streetsblog. (2017). [Available here]

13. The Costs of Affordable Housing Production: Insights from California’s 9% Low-Income Housing Tax Credit Program, Carolina Reid, Terner Center for Housing Innovation, UC Berkeley. (2020). [Available here]

14. Affordable Parking Housing Study, City of San Diego. (2011). [Available here]

15. The Fundamental, Global Law of Road Congestion, Joe Cortright, City Commentary. (2021). [Available here]

16. Cruising for Parking, Donald Shoup, ResearchGate (2018). [Available here]

17. Local Water Policy Innovation, American Rivers & Midwest Environmental Advocates (2008).

18. No Parking? No Problem. Now Let’s Build for People Too, Kuanyu Chen, CityBuilder. (2025). [Available here]

19. In Memoriam: Donald Shoup, Renowned UCLA Urban Planner and Parking Reform Pioneer, Stan Paul, UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs. (2025). [Available here]

20. Minneapolis May Drop Parking Minimums Near Transit, Brad Aaron, Streetsblog USA. (2015). [Available here]

21. SFpark evaluation, San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency. (n.d.). [Available here]

22. How Washington State Won Parking Reform, Catie Gould, Sightline Institute (2025). [Available here]

23. Minus Minimums: Development Response to the Removal of Minimum Parking Requirements in Buffalo (NY), Daniel Baldwin Hess & Jeffrey Rehler, Journal of the American Planning Association (2021). [Available here]

24. Parking policy: The effects of residential minimum parking requirements in Seattle, C.J. Gabbe, Gregory Pierce, Gordon Clowers, Land Use Policy (2020). [Available here]

25. Do CT towns and cities have too much parking? Some advocates hoping for parking mandate reform say yes, Michael Walsh, CT Insider. (2025). [Available here]

26. 30,000 people can fit in the space taken by this Houston highway intersection, Jay R. Jordan, Chron.com (2020). [Available here]

27. Europe’s Parking U-Turn: From Accommodation to Regulation, Michael Kodransky & Gabrielle Hermann, Institute for Transportation & Development Policy. (2011). [Available here]

28. Berlin parking: model or warning, Paul Barter, Reinventing Parking. (2018). [Available here]

29. The London Plan: Spatial Development Strategy for Greater London. Mayor of London. (2004). [Available here]

30. Car-free residential zones in the city. Stadt Wien. [Available here]

31. How the Netherlands handles parking, Paul Barker, Reinventing Parking. (2022). [Available here]

32. The sustainable Urban district of vauban in Freiburg, Germany, Gary Koates, International Journal of Design & Nature and Ecodynamics. (2013). [Available here]

33. Paris approves making 500 streets car-free, Annabelle Timsit, The Washington Times. (2025). [Available here]

34. New TfL data shows cycling journeys in London are up by 26 per cent compared to 2019 levels, Transport for London. (2024). [Available here]

35. Bollards and ‘superblocks’: how Europe’s cities are turning on the car, Jon Henley, Steven Burgen & Lisa O’Carroll, The Guardian. (2023). [Available here]

36. Oslo Is (Almost) Car-Free – And Likes It That Way, Derek Markham, CleanTechnica. (2019). [Available here]

37. Brussels starts to remove through traffic from its city centre, European Commission: EU Urban Mobility Observatory. (2022). [Available here]

38. Parking Benefit Districts, Donald Shoup, Journal of Planning Education & Research. (2023). [Available here]

39. Ideas Worth Stealing: Parking benefit districts, Jon Geeting, WHYY. (2016). [Available here]

40. Parking and Sustainable Urban Mobility Planning: How to make parking policies more strategic, effective and sustainable, European Commission. (2022). [Available here]

41. If John Locke Pulled Up to the Curb and Found No Space, Norm Van Eeden Petersman, Strong Towns. (2025). [Available here]